Rory Murray, Staff Writer |

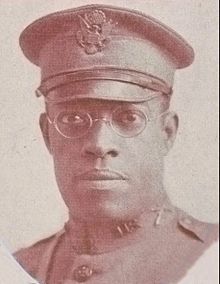

Born in 1890 in Mobile, Alabama, James Reese Europe was an American ragtime and early jazz bandleader, arranger, and composer. He was a prominent figure in the African American music scene in New York City in the 1910’s and his military band, the 369th Regiment Hellfighters, brought music across Europe during World War I.

In 1910, Europe started an organization for African American musicians called the Clef Club, which served as a concert hall for African Americans as well as a fraternal organization to help musicians network and find gigs to play. Along with this, Europe started the Clef Club orchestra, which was the first all African American orchestra and boasted over 125 members. His orchestra is famous for its 1912 concert at Carnegie Hall, considered the first time popular music was played in Carnegie Hall. The concert was so well received that the orchestra returned again in 1913 and 1914. The Clef Club was very successful, earning around $100,000 a year at its height in bookings.

The Clef Club orchestra achieved national recognition in 1912 as the accompaniment for theatre dancers Vernon and Irene Castle, who are credited with teaching America how to dance from the waist down. The Castles did more than just teach America how to “Foxtrot”—they provided James Reese Europe’s all-black orchestra exposure to a white audience.

Throughout 1913 and 1914, Europe’s orchestra made a series of recordings that are some of the best examples of the pre-jazz hot ragtime style, though they were not marketed as jazz, and Europe is not attributed with creating the first jazz record. His early recorded work is not considered jazz because his style, though quite similar to the early jazz around that time, was too proper for early jazz. Jazz bands at the time were often fairly small and all of the music was memorized or improvised by the musicians, whereas Europe’s orchestra had 125 members and the music was strictly composed with no room for improvisation.

During World War I, James Reese Europe was a lieutenant in 369th Army Regiment known as the “Harlem Hellfighters,” a name granted by the Germans because they never lost a soldier to capture nor a foot to their trench. The success of this army regiment helped to change public opinion about African American soldiers. Europe directed the marching band for this army regiment, which introduced jazz to continental Europe, and the band was highly regarded for their ability to boost the morale of the troops.

While Europe was in France, a French band leader asked him for one of his arrangements so that his band could play some “American Jazz.” The next day, the band leader came back to Europe upset that it did not sound like the jazz he had heard Europe’s band play and even believed that their instruments were altered to make them sound the way they did. The French band did not understand the subtle nuances that make jazz sound like jazz and were only focused on the notes upon the paper that James Reese Europe gave him.

After the war, the 369th Army Regiment returned to New York with great honor and glory, parading through the streets of the city on February 12, 1919. This date, though never officially recognized, became a holiday of great remembrance for those in Harlem and African Americans across the country. The 369th marching band began a national tour after their return, with the final concert held in Boston on May 9. The final concert of this tour was unfortunately James Reese Europe’s last performance; an argument with one of Europe’s drummers resulted in the drummer stabbing the bandleader in the neck with a pen. He was dead the next morning.

James Reese Europe’s legacy did not die with him—the success of the Harlem Hellfighters during World War I and the fame of his marching band showed America that black soldiers fought just as well as the white ones. This began the long road of desegregation within the military, with black soldiers moving away from the lowest jobs available, including suicide missions. Europe also is partially responsible for jazz coming to New York, and he helped countless African American musicians find jobs as well as the compensation and treatment they rightfully deserved by establishing the Clef Club. This Black History month, we remember Europe’s legacy and impact on African American music.

Leave a Reply