Richie Feathers, Managing Editor

At first, the punk movement of the mid 1970s didn’t have a name, just a feeling. To those most affected by it–British teens of the working-class and bored American suburbanites–punk was a wild escape. It grabbed hold of their frustration and pent up energy and told them to start a band, where amateurism was key.

As my own frustration about a looming uncertainty stirs around some newfound urge to never be sitting during these final days of college, I’ve found myself drawn to and inspired by the punk movement. I could be romanticizing a period that sounds incredibly exciting, but I also think the historical climate that punk was born from isn’t that distant from our own.

In my opinion, us millennials have a lot more in common with the early punks than the 60s flower children we aspire to be. As with everything else following 60 years of rock and roll, we’re certainly a hybrid generation. But our environment and the way we interact with each other parallel two major roots of the punk movement.

In the dazed aftermath of 60s free love and radical activism, the 70s hung heavy on the adults and gave American youths little to be passionate about. Punk, if nothing else, gave its players something to do.

As Nils Stevenson, Manager of Siouxsie and the Banshees said, “There was a sense of individuality, expressing yourself. You didn’t think–it was instinctive.”

Our lack of enthusiasm and outright boredom was most recently expressed by none other than Taylor Swift–“We’re all bored/We’re all so tired of everything/We wait for trains that just aren’t coming,” she sings in “New Romantics.” Swift, arguably one of the most influential figures of our generation, is telling us what we already know: We’re looking for something to do, too.

Think of the first 10 years of the 21st century as our own decade of free thinking, our own 1960s. For one, the strides we made in technology are mind-boggling. iPhones, iPods, iTunes–Apple revolutionized the way we conduct business and communicate–not to mention they singlehandedly altered the music industry forever.

But now, halfway through the second decade, we’ve gotten used to nifty tricks, the exciting-at-first features of the iPhone-of-the-moment. We’ve resorted to anxiously waiting in line for the release of a watch. In other words, we’ve grown bored.

Our generation’s concerns about finding jobs also mirror those of the young Brits who turned to punk for an outlet. Growing up in working-class towns on the outskirts of major cities, for them, bright futures were all but expected. For us, degrees are practically required to get a job, which means about a fifth of our lives, and all of our money, is spent on school. So, who can blame us for feeling disenfranchised with “The Establishment” when we’ve never known anything else?

In Britain especially, inspired by glam icons like David Bowie (read: Lady Gaga) and bad boy rock heroes the Rolling Stones, punk was the answer and the rebuttal to authority and any law and order. It encouraged opposition to the bloated progressive rock giants whose only connection with the audience was through a projector. (Take a peek at any major label tour schedule of 2015 and you’ll see similarly-sized venues.)

Punk’s do-it-yourself guidelines brought music back to the clubs and rock back to garages, and everyone could give it a try.

With all of the small, broke touring acts currently moving through bars and tiny auditoriums, this idea of a stripped performance is still very much alive. And the amount of bands that our technology has given voice to, from electronic and indie-pop, to rock and folk, resembles the surge of fast-playing punk bands that tore through the streets trying to find gigs.

Some teens started homemade fanzines with comic book-style pictures and personal interviews. Minus the creativity, these magazines, and others like MAD Magazine, resemble a widely-read news source similar to the style of BuzzFeed. And local gossip was often traded in clothing stores, which were the social hotspots that coffee shops are to us, and in the seedy bars where they’d see their friends play.

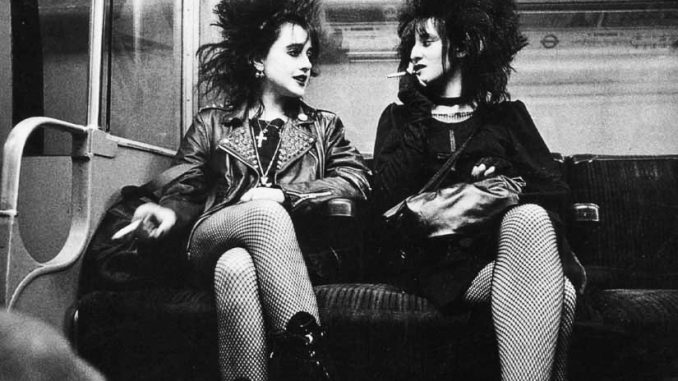

Punks would congregate, dressed in tight leather and offensive language, mingle and began to influence each other. And with all the shows to make, they also found new ideas in their peers’ music. Soon, a web formed through the bands whose drummer used to play bass in another or whose singer was just kicked out of his own band.

I find this interconnectedness similar to social media.

Of course, the punk movement didn’t last forever. Once it found a title and stepped out of the underground, recording contracts and mainstream success cut short that initial feeling of do-it-yourself immediacy. And after a headline-grabbing interview with the controversial Sex Pistols (read: Kanye West), parents disapproved of their kids’ music and icons, further widening the generation gap.

While it was here however, one of the most interesting things about punk was that it happened in Britain and the United States at the same time, without much communication between the two. It was a chain reaction to not only their external environments but to their internal period of adolescent transition as well.

It’s this natural transition that us graduates are facing head on.

So, what can comparing our society to those of British and American punks do to ease this transition?

Probably nothing–these next few months and years are bound to be challenging regardless.

But the feeling of punk still ripples through the same age group it once did, and it’s our turn to take hold of it. I’m not insisting that everyone starts a band, I’m insisting we all look to the wild spirit from which so many formed.

“Punk was like we didn’t have a map and we didn’t have an address,” Sham 69 vocalist Jimmy Pursey said. “It was like someone nicking a car and saying, ‘Who’s coming?’”

While each era of the music history can put our own society into perspective, I think we can learn a lot from the punk movement. The society we’re growing up in is different than the 1970s, but us twenty-somethings are not. Feel your frustration, cultivate your energy and find your voice.

So, who’s coming?

Leave a Reply