Cheyenne Dorsagno, Editor-in-Chief |

Americans everywhere decry their broken education system, with fingers pointing at “ineffective” methods, “disrespectful” students, “overpaid” teachers, “neglectful” federal funding, an “out of date” curriculum, as well as other objects of blame and speculation.

While an education system can never be perfect, the U.S. has been tragically underperforming in comparison to other developed nations.

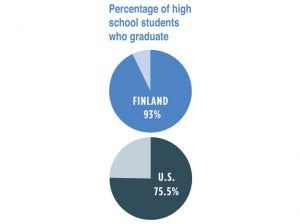

The Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) globally evaluates 15-year-old students’ reading, math, and science literacy every three years. Finland and South Korea have consistently been found at the top of these rankings, while the United States has lagged behind, landing 41st place, a below average score, in the most recent 2015 Math assessment.

The U.S. has tried to combat national criticism by enacting the 2001 “No Child Left Behind Act,” requiring that teachers make nearly all of their students meet a certain standard and maintain annual growth. Many regarded this as an impossible feat, because not all students are “average,” and teachers cannot miraculously develop young minds (as if that has not always been their goal) without a drastic change in the system they must operate through. This Act has since been replaced with the 2015 Every Student Succeeds Act, drawing back impunity and giving more power to the states, which will create their own accountability and evaluation procedures for teachers.

In 2016, some school districts, such as that of Greenville County, South Carolina, banned zero grades in their middle school – even if students cheat, do not turn in their work, or do not attend class. Instead, a student is given a failing grade of 61. Some have emblazoned this approach under a philosophy of “good faith,” in which any student must have put in enough effort to earn some credit, regardless of their actual knowledge. Others say that a zero is too destructive and discouraging.

U.S. attempts to resolve their failing education system have been ambitious, but overall simplistic, superficial, and unhelpful. At times, it just comes down to fudging numbers and passing along ill-prepared children. With teachers facing punishment and school districts competing for funding, it is easy to see why.

So what are Finland and South Korea doing right? Sometimes, it is hard to say, given these countries have nearly polar opposite approaches to education, as shown in the documentaries “The Finland Phenomenon” and “School Swap: Korea Style.”

In Finland, students spend around 600 hours/year in a relaxed environment, calling their professors by their first name and incorporating the arts into every subject. Finnish schools offer flexible schedules to cater to the students’ learning pace and sleeping habits. In South Korea, creativity is squelched, and high schoolers might spend as many as 13 hours at school in one day, with 192 school days/year. They only address their educators as “teacher,” standing and bowing out of respect whenever a professor enters or leaves the room.

In Finland, there is little homework and testing so that students can individually utilize their unique learning style. There may be more than one teacher in a room so that slower-learning students can have individual attention. The majority of the lessons are interactive and led by student discussion. In South Korea, midterms and final tests count for 70 percent of the class grade. A single eight-hour college entrance exam is given nationwide every year, and the classroom is largely led by the teachers’ lectures.

Similar to South Korea, the U.S. teaches through lecturing and testing. However, this approach only seems to work when the students are living and breathing school, a lifestyle that has led many South Korean youths to commit suicide. In Finland, the educational experience is personalized, effective, and efficient. People wonder what stops kids from learning: not eating lunch, waking up too early, over emphasizing testing? Finland has resolved all of these speculations.

So what do Finland and South Korea have in common? Could this commonality be the key to their success?

For one, Finland and South Korea make sure that every student has an equal opportunity for a quality education. Students have the materials and the funding that they need. However, in Pennsylvania, per-pupil spending in the poorest school districts is 33 percent lower than per-pupil spending in the wealthiest school districts, according to The Washington Post. Poor students and poorly funded school districts often have a worse academic outcome.

Of course, America has a lot of children learning English as a second language, which reasonably lowers the average. Children living in poor communities may not see school as a solution to their problems, or they may not have the immediate resources to continuously follow through with school as a long-term investment.

Furthermore, Chief Education Adviser at Pearson, Sir Michael Barber, told BBC that countries ranking high on the PISA exams often have a “culture” of education in which teaching is a high-status job. Although Finland and South Korea have stark differences, there is a shared social belief in the importance and “underlying moral purpose” of education. Conversely, a 2010 McKinsey study of America’s top graduates’ attitudes toward teaching shows that only 66 percent of respondents “would be proud” to tell people that they are a teacher, while only 37 percent said that teachers are “considered successful.”

Finland touts a culture of “trust,” and South Korea similarly leaves it up to the professors to create effective lesson plans. While both countries have a standard curriculum, professors have more time and freedom to plan their lessons. In these countries, professors can gain constructive criticism from their coworkers as opposed to undergoing administrative evaluations like American professors. In the U.S., teachers are oftentimes limited in what content and in what way they can teach.

“Research tells us that schools improve most when teachers are empowered. This includes reforms like increasing paid time for teachers to plan intellectually engaging lessons, letting them design their own assessments, and reflecting on student work to adjust their teaching,” according to Mother Jones.

Additionally, 100 percent of teachers in South Korea and Finland come from the top third of college graduates. In these countries, teaching is a competitive field with an abundance of pursuers. In America, only 23 percent of teachers come from the top third of their class, and this is likely due in part to the teacher shortage in the U.S. According to The Washington Post, U.S. enrollment in teacher-preparation programs has dropped 35 percent. By their fifth year, almost half of America’s teachers will leave the profession.

If teachers aren’t being respected, trusted, and appreciated, it’s easy to understand why the profession is under-pursued and often short lived. In America, it is not entirely uncommon for a teacher to be called a “bitch” by a student or for the entire class to harp the educator, perhaps criticizing their methods, asking them to postpone a due date, or questioning their interest in the students’ success. Parents may angrily contest their child’s grades or bawl to teachers about the social importance of not holding their child back a grade. Students often complain about being assigned homework as if their educators are setting them up to fail, and some professors have lessened their assignments in appeasement.

Of course, there will always be some bad teachers in the bunch. And as warranted as current distrust of authority may be, some fail to see that most teachers have dedicated their lives to fostering young minds. American educators certainly aren’t in it for the prestige.

Disrespect toward teachers may be due in part to the recent American cultural ideal of “anti-intellectualism.”

On television, studious children are often portrayed as “nerds” and “teachers’ pets.” Sometimes, politicians refrain from scaring Americans with a large vocabulary or boring political plans. In Reagan’s 1964 speech “A Time for Choosing,” he compared himself to the ordinary American rather than the “little intellectual elite in a far-distant capitol.” People proclaim “false news” or “alternative facts” to accommodate their opinions as needed, and college curricula have been accused of perpetuating a liberal agenda. According to USA Today, over half of today’s youth realize that a college education is becoming increasingly important to advance in the world. However, many students see school as a mandatory hurdle to success as opposed to a privilege, a rewarding experience, and a helpful tool in one’s personal life.

PLEASE SEE THE PERSONAL NOTE BELOW AND GO TO THE FOLLOWING LINK TO GET A PROFESSOR’S PERSPECTIVE ON THIS ISSUE: www.thestatetimes.com/?p=11128

Front Row: Akira Yatsuhashi, Department Chair Dan Payne, Amie Doughty, Kathryn Finin, Konstantina Karageorgos

Missing from picture: Susan Bernardin, Richard Lee, and Mark Ferrara

Oneonta.edu

PERSONAL NOTE:

On a personal note, I do not doubt the drive and perseverance of many American students. Having gone to a large high school, there was a huge disparity between the worst and best performing students. My boyfriend often complained about the lack of productivity of his non-regents Chemistry class while I was taking college-level Advanced Placement classes at 14-years-old. My boyfriend and I went to the same school, and yet our experiences were so different. I have been fortunate to have these opportunities, and my peer group was extremely competitive. College is not meant for everyone, and it is not the only way to succeed, but I believe that access to quality childhood education should be one of the most highly prioritized values in our country.

I would like to thank all of the teachers that I have had, especially those at the SUNY Oneonta English Department. They have a depth of passion and knowledge that excited me for the class material. Professors have taken a lot of personal time to encourage me, meet me at their office, review my work, write me recommendations, etc., etc. The content of their courses has not only educated me, but challenged me to be analytical of the world around me. My professors have helped me develop my values and points of view, and the information they have given me has equipped me to make well-informed decisions both in my career and in my personal life. I have great respect, appreciation, and admiration for my professors. I will carry their support with me for the rest of my life.

Leave a Reply