Richie Feathers, Managing Editor

One of the essential qualities music listeners expect from an artist is honesty. It isn’t hard to come by, especially in an age when omission means the same as lying. But on his new album Carrie & Lowell, Sufjan Stevens shows just how special it is when true honesty is given so vulnerably.

One of the essential qualities music listeners expect from an artist is honesty. It isn’t hard to come by, especially in an age when omission means the same as lying. But on his new album Carrie & Lowell, Sufjan Stevens shows just how special it is when true honesty is given so vulnerably.

A man who once turned a song about serial killer John Wayne Gacy into a harrowing tearjerker, Stevens has always strung his quieter tunes with lines of aching beauty. Yet, while his eccentric catalog covers themes from Chinese zodiac symbols, to the state of Michigan, to annual Christmas carols, it’s on Carrie & Lowell, a stark, bedroom folk album, where Stevens’ gifts as an honest songwriter are the most disarming.

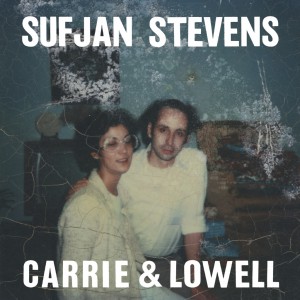

Named after his mother and step father, the record charts the 39-year-old’s struggle following the death of his mother, who abandoned the family a year after Stevens was born. Although Carrie remained a sporadic part of his life, including childhood summers spent in Oregon with her and Lowell, it was fraught with illness–she suffered from schizophrenia, depression and alcoholism.

Stevens’ fractured relationship with Carrie tints every track on the album. Throughout, the singer stretches himself between feelings of longing, guilt and betrayal, but never tears at the seams. His spectral whisper holds it all together as shards of childhood memories mingle with suicidal thoughts and self-sabotaging behavior following Carrie’s death.

The finger-picking folk of “Eugene” shares stray images of years long gone, Stevens begging, “Now I want to be near you,” like a child tugging on his mother’s apron. In “The Only Thing” he nearly drives off the road, giving in to numbness, asking, “Do I care if I survive this?/I wonder did you love me at all?”

In lesser hands, these fragile themes could have twisted into heavy-handed morbidity and outright masochism. Stevens, though, isn’t looking for pity or recognition; he’s talking himself through a process he wasn’t prepared for.

“It’s something that was necessary for me to do in the wake of my mother’s death,” Stevens said in a recent interview. “[T]o pursue a sense of peace and serenity in spite of suffering.”

He finds it in “Should Have Known Better,” where uprooted memories of being left at a video store are replanted with the prospect of new life (“My brother had a daughter/The beauty that she brings, illumination”); and in the lovely “Death With Dignity,” where he offers forgiveness to his absent mother.

But because much of Carrie & Lowell is about the journey itself to finding that acceptance, the detours in despair get under the listener’s skin.

The tragic “Fourth of July” weaves together Stevens’ last words with Carrie and his final look at her body, and in “All of Me Wants All of You” he sinks into passionless sex.

Lead single “No Shade In the Shadow of the Cross” is an unassuming powerhouse, the singer audibly crumbling under the weight of saying goodbye to a mother he never really knew. “There’s blood on that blade,” he weeps. “Fuck me, I’m falling apart.”

Such concentrated grief places Carrie & Lowell alongside other classic albums that were born from tragedy–from Bob Dylan’s Blood On the Tracks to Bon Iver’s For Emma, Forever Ago. With swollen hearts, there’s little room for much more than their thoughts.

“It feels artless,” Stevens said of the record, “which is a good thing. This is not my art project; this is my life.”

Key Tracks: “No Shade In the Shadow of the Cross,” “John My Beloved,” “Fourth of July”

Leave a Reply